Final Report 2012

Executive Summary

History

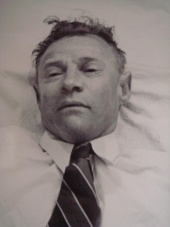

On December 1st 1948, around 6.30 in the morning, a couple walking found a dead man lying propped against the wall at Somerton Beach, south of Glenelg. He had very few possessions about his person, and no form of identification. Though wearing smart clothes, he was without a hat (an uncommon sight at the time), and there were no labels in his clothing. The body carried no form of identification, his fingerprints and dental records didn’t match any international registries. The only items on the victim were some cigarettes, chewing gum, a comb, an unused train ticket and a used bus ticket.

The coroner's verdict on the body stated that he was 40-45 years old, 180 centimetres tall, and in top physical condition. His time of death was found to be at around 2 a.m. that morning, and the autopsy indicated that, though his heart was normal, several other organs were congested, primarily his stomach, his kidneys, his liver, his brain, and part of his duodenum. It also noted that his spleen was about 3 times normal size, but no cause of death was given, the coroner only expressing his suspicion that the death was not natural and possibly caused by a barbiturate. 44 years later, in 1994 during a coronial inquest, it was suggested that the death was consistent with digitalis poisoning

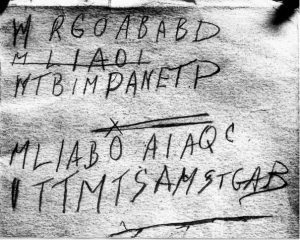

Of the few possessions found upon the body, one was most intriguing. Within a fob pocket of his trousers, the Somerton Man had a piece of paper torn from the pages of a book, reading "Tamam Shud" on it. These words were discovered to mean ``ended or ``finished in Persian, and linked to a book called the Rubaiyat, a book of poems by a Persian scholar called Omar Khayyam. A nation-wide search ensued for the book, and a copy was handed to police that had been found in the back seat of a car in Jetty Road, Glenelg, the night of November 30th 1948. This was duly matched to the torn sheet of paper and found to be the same copy from which it had been ripped.

In the back of the book was written a series of five lines, with the second of these struck out. Its similarity to the fourth line indicates it was likely a mistake, and points towards the lines likely being a code rather than a series of random letters.

WRGOABABD

MLIAOI

WTBIMPANETP

MLIABOAIAQC

ITTMTSAMSTGAB

Introduction

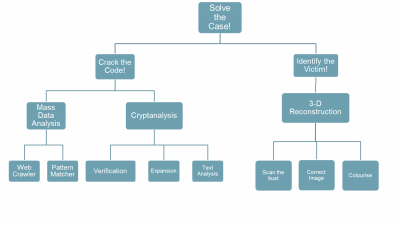

For 60 years the identity of the Somerton Man and the meaning behind the code has remained a mystery. This project is aimed at providing an engineer’s perspective on the case, to use analytical techniques to decipher the code and provide a computer generated reconstruction of the victim to assist in the identification. Ultimately the aim is to crack the code and solve the case. The project was broken down into two main aspects of focus, Cipher Analysis and Identification, and then further into subtasks to be accomplished:

The first aspect of the project focuses on the analysis of the code, through the use of cryptanalysis and mathematical techniques as well as programs designed to provide mass data analysis. The mathematical techniques looked at confirming and expanding on the statistical analysis and cipher cross off from previous years. The mass data analysis expanded on the current Web Crawler, pattern matcher and Cipher GUI to improve the layout and functionality of these applications. The second aspect focuses on creating a 3D reconstruction of the victim’s face, using the bust as the template. The 3D image is hoped to be able to be used to help with the identification of the Somerton Man. This aspect of the project is a new focus, that hasn’t previously been worked on. The techniques and programs we have been using have been designed to be general, so that they could easily be applied to other cases in used in situations beyond the aim of this project.

Motivation

For over 60 years, this case has captured the public's imagination. An unidentified victim, an unknown cause of death, a mysterious code, and conspiracy theories surrounding the story - each wilder than the last. As engineers our role is to solve problems that arise, and this project gives us the ideal opportunity to apply our problem solving skills to a real world problem, something different from the usual "use resistors, capacitors and inductors" approach in electrical \& electronic engineering. The techniques and technologies developed in the course of this project are broad enough to be applied to other areas; pattern matching, data mining, 3-D modelling and decryption are all useful in a range of fields, or even of use in other criminal investigations such as the (perhaps related) Joseph Saul Marshall case.

Project Objectives

The ultimate goal of this project is to help the police to solve the mystery. Whilst this is a rather lofty and likely unachievable goal, by working towards it we may be able to provide useful insights into the case and develop techniques and technologies that are applicable beyond the scope of this single case. We have taken a multi-pronged approach to give a broader perspective and draw in different aspects that, taken in isolation, may be meaningless but taken as a whole become significant. The two main focuses of this project are cracking the code found in the Rubaiyat, and trying to identify the victim. To further break down cracking the code, the web crawler and pattern matcher are used to trawl the internet for meaning in the letters of the code, and directly interrogating the code with various ciphers to try and find out what is written. In order to be able to identify the victim so long after his death, we need to recreate how he might have looked when he was alive, firstly by making a three-dimensional reconstruction from a bust taken after he was autopsied, and then by manipulating the resulting model to create a more life-like representation, complete with hair, skin and eye colours (which can be found in the coroner's report).

Previous Studies

Previous Public Investigations

During the course of the police investigation, the case became ever more mysterious. Nobody came forward to identify the dead man, and the only possible clues to his identity showed up several months later, when a luggage case that had been checked in at Adelaide Railway Station was handed in. This had been stored on the 30th November, and it was linked to the Somerton Man through a type of thread not available in Australia but matching that used to repair one of the pockets on the clothes he wore when found. Most of the clothes in the suitcase were similarly lacking labels, leaving only the name "T. Keane" on a tie, "Keane" on a laundry bag, and "Kean" (no 'e') on a singlet. However, these were to prove unhelpful, as a worldwide search found that there was no "T. Keane" missing in any English-speaking country. It was later noted that these three labels were the only ones that could not be removed without damaging the clothing. \cite{wiki12}

At the time, code experts were called in to try to unravel the text, but their attempts were unsuccessful. In 1978, the Australian Defence Force analysed the code, and came to the conclusion that:

- There are insufficient symbols to provide a pattern

- The symbols could be a complex substitute code, or the meaningless response to a disturbed mind

- It is not possible to provide a satisfactory answer \cite{wiki12}

What does not help in the cracking of the code is the ambiguity of many of the letters.

As can be seen, the first letters of both the first and second (third?) lines could be considered either an 'M' or a 'W', the first letter of the last line either an 'I' or a 'V', plus the floating 'C' at the end of the penultimate line. There is also some confusion about the 'X' above the 'O' in the penultimate line, whether it is a part of the code or not, and the relevance of the second, crossed-out line. Was it a mistake on the part of the writer, or was it an attempt to underline (as the later letters seem to suggest)? Many amateur enthusiasts since have attempted to decipher the code, but with the ability to "cherry-pick" a cipher to suit the individual it is possible to read any number of meanings from the text.

Previous Honours Projects

This is the fourth year for this particular project, and each of the previous groups has contributed in their own way, providing a useful foundation for the studies undertaken this year and into the future.

2009

The original group from 2009, Andrew Turnbull and Denley Bihari, focused on the nature of the "code". In particular, they looked at whether it even warranted investigation - could it just have been the random ramblings of an intoxicated mind? Through surveying people, both drunk and sober, they established that the letters were significantly different from the frequencies generated by a population sample, and weren't likely to be random. Given the suggestion that the letters had some significance, they set about establishing what that significance was. They considered the possibility that the letters represented the initial letters of an unordered list, and this was shown to have some merit. They also tested the theory that the letters were part of a transposition cipher - where the order of letters is simply swapped around, as in an anagram - but the relative frequencies of the letters (no 'e's whatsoever for example) suggested this was unlikely. After discounting transposition ciphers, they looked at the other main group of ciphers - substitution ciphers, where the letters of the original message are replaced with totally different ones. They were able to discount Vigenere, Playfair, Alphabet Reversal and Caesar ciphers, and examined the possibility the code used a one-time pad that was the Rubaiyat or the Bible, though these were eliminated as candidates. Finally, they attempted to establish the language the code was written in, and in a comparison of mainly Western-European languages found that English was the best match by scoring the languages using Hidden Markov Modelling. Based on this, they discovered that, with the ambiguity in some of the letters, the most likely intended sequence of letters in the code is actually:

WRGOABABD

WTBIMPANETP

MLIABOAIAQC

ITTMTSAMSTCAB

2010

In the following year, Kevin Ramirez and Michael Lewis-Vassallo verified that the letters were indeed unlikely to be random by surveying a larger number of people to improve the accuracy of the letter frequency analysis, with both more sober and more drunk participants. They further investigated the idea that the letters represented an initialism, testing against a wider range of texts and taking sequences of letters from the code to do comparisons with. They discovered that the Rubaiyat had an intriguingly low match, suggesting that it was made that way intentionally. From this they proposed that the code was possibly an encoded initialism based on the Rubaiyat.

The main aim for the group in 2010 was to write a web crawler and text parsing algorithm that was generalised to be useful beyond the scope of the course. The text parser was able to take in a text or HTML file and find specific words and patterns within that file, and could be used to go through a large directory quickly. The web crawler was used to pass text directly from the internet to the text parser to be checked for patterns. Given the vast amount of data available on the internet, this made for a fast method for accessing a large quantity of raw text to be statistically analysed. This built upon an existing crawler, allowing the user to input a URL directly or a range of URLs from a text file, mirror the website text locally, then automatically run it through the text parsing software. \cite{fyp10}

2011

In 2011, Steven Maxwell and Patrick Johnson proposed that there may already exist an answer to the code, it just hasn't been linked to the case yet. To this end, they further developed the web crawler to be able to pattern match directly, an exact phrase, an initialism or a regular expression, and pass the matches on to the user. When they tested their "WebCrawler", they did find a match to a portion of the code, "MLIAB". This turned out to be a poem with no connection to the case, but shows the effectiveness and potential for the WebCrawler. \cite{mliab84}

They also looked to expand the range of ciphers that were checked, and wrote a program that performed the encoding and decoding of a range of ciphers automatically, allowing them to test a wide variety of ciphers in a short period of time. This also lead them to use a "Cipher Cross-Off List" to keep track of which possibilities had been discounted, which were untested, and which had withstood testing to remain candidates. By using their "CipherGUI" and this cross-off list, they were able to test over 30 different ciphers, and narrow down the possibilities significantly - only a handful of ciphers were inconclusive, and given the time period in which the Somerton Man was alive, more modern ciphers could automatically be discounted. \cite{fyp11}

Structure of this Report

With so many disparate objectives, each a self-contained project within itself, the rest of the report has been divided into sections dedicated to each aspect. There is then a section on how the project was managed, including the project breakdown, timeline and budget, and the sections are finally brought back together in the conclusion, which also indicates potential future directions that this project could take.

Methodology

Statistical Analysis of Letters

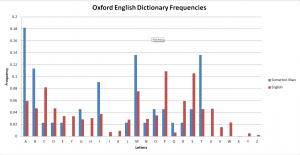

The initial step within this project, involved reviewing the previous work accomplished by other projects and to set up tests that would confirm the results found were consistent. The main focus for verification involved the analysis performed on the code, and the statistical analysis that lead to these results. The results from previous years suggested that the code was most likely to be in English, and represented the initial letters of words. To test this theory and to create some baseline results, the online Oxford English Dictionary was searched and the number of words for each letter of the alphabet was extracted. From this data, the frequency of each letter being used in English was calculated, and resulted in the graph shown in figure 3.1.1. [7]

The results show that there were many inconsistencies with the Somerton Code, but can be used as a baseline for comparison with other results. The main issue with the results produced, is that most of the words that were included are not commonly used, and as such are a poor representation of the English language. Therefore the likelihood of them being used is not related to the number of words for each letter. In order to produce some useful results for comparison a source text was found which had been translated into over 100 different [8]. The text was the Tower of Babel passage from the Bible, and consisted of approximately 100 words and 1000 characters; which allowed it to be a suitable size for testing. In order to create the frequency representation for these results a java program was created which would take in the text for each language, and output the occurrence of each of the letters. This process was repeated for 85 of the most common languages available and from this data, the standard deviation and sum of difference to the Somerton Man Code was determine.

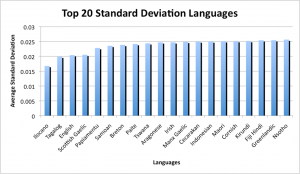

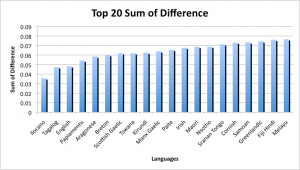

The results were quite inconsistent with previous results, as well as each other. The top four results for both the standard deviation and sum of difference were: Sami North, Ilocano, White Hmong and Wolof; but were in different orders. These languages are all geographically inconsistent as they represent languages spoken in Eastern Europe, Southern Asia and Western Africa. This suggests that these aren’t likely to represent the language used for the Code. Previous studies suggested that the Code represents the initial letters of words, so this theory was tested as well. The process from before was repeated, with a modified java program which would record the first letter of each word within the text. From these results, the frequencies of each letter occurring was calculated, with the results shown in figures 3.1.4 and 3.1.5.

The results described in the figures above, provide more consistent results from before. The top three languages for both the sum of difference and standard deviation were, in order: Ilocano, Tagalog and English. The first two languages are from the Philippines, and since all the other information about the Somerton Man suggests he is of "Britisher" appearance, it is unlikely that he spoke either of these languages. This leaves English as the next likely, as it is the most consistent with the information known about both the code and the Somerton Man. This also reinforces the results that the code most likely represents the first letters of an unknown sentence and is consistent with results from previous years.

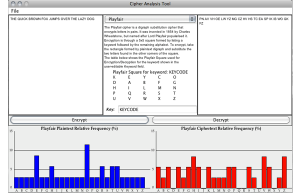

Cipher GUI

In the course of evaluating a range of different ciphers, the group last year developed a Java program which could both encode and decode most of the ciphers they investigated. Part of our task this year was to double-check what they had done. To do this, we tested each cipher with both words and phrases being encoded and decoded, to look for errors. Whilst most ciphers were faultless, we discovered an error in the decryption of the Affine cipher that lead to junk being returned. We investigated possible causes of the error, and were able to successfully resolve a wrapping problem (going past the beginning of the alphabet C, B, A, Z, Y... was not handled correctly), so now the cipher functions correctly both ways.

We also sought to increase the range of ciphers covered. One example we found was the Baconian Cipher, whereby each letter is represented by a unique series of (usually 5) As and Bs (i.e. A = AAAAA, B = AAAAB, and so on). Whilst this was known of during the Somerton Man's time, the use of letters besides A and B in the code clearly indicates the Baconian Cipher was not used. Despite this, the Baconian Cipher would have made a useful addition to the CipherGUI. However, the nature of the way it was coded, and our lack of familiarity with the program, made the addition of further ciphers difficult, so we decided to focus our efforts on other aspects of the project.

Last year's group did a lot of good work developing a "Cipher Cross-off list", which went through a range of encryption methods and determined whether it was likely or not that the Somerton Man passage had been encoded using them. We analysed their conclusions, and for the most part could find no fault with their reasoning. However, they dismissed "One-Time Pads" wholesale, arguing that the frequency analysis of the code did not fit that of an OTP. However, they assumed that the frequency analysis of the OTP would be flat, since a random pattern of letters would be used. This is fine for most purposes, but if the Somerton Man had used an actual text - for example the Rubaiyat - then its frequency distribution would not be flat. It is for all intents and purposes impossible to completely discount OTPs as the source of the cipher, since the possible texts that could have been used - even ignoring a random sequence of letters - is near infinite. You cannot disprove something for which no evidence exists; you can only prove its existence by finding it.

Future Development

Project Management

Timeline

Budget

Risk Management

Project Outcomes

Significance and Innovations

Strengths and Weaknesses

Conclusion

References

See Also

- Glossary

- Progress Report 2012

- Cipher Cross-off List

- CipherGUI 2011 (Download)

- Web Crawler 2011 (Download)

- 2011 Project Video (YouTube)

- 2011 Final Seminar Part 1 (YouTube)

- 2011 Final Seminar Part 2 (YouTube)

- 2011 Final Seminar Part 3 (YouTube)

References and useful resources

- Final Report 2011

- Final Report 2010

- Final report 2009: Who killed the Somerton man?

- Timeline of the Taman Shud Case

- The taman shud case